Zombie Companies: Buying Opportunity or Economic Ballast

There are three ideas that M&A managers handle as a result of the crisis caused by COVID in the economy, namely: that many companies are holding out thanks to the help of banks, that when all of this ends, the vulnerable companies will disappear and that we have to have cash to take advantage of the opportunities that these companies offer us.

We are going to delve into the first two ideas and leave the third of them for the next article. And we are going to do it based on what we know about companies in difficulty, the so-called zombie companies.

First of all, what is meant by zombie companies?

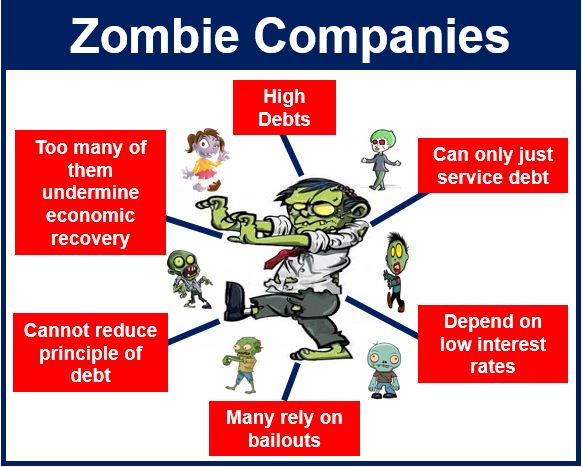

They are those very vulnerable and that are subsisting thanks to the capital lent by the banks, those whose business model in the medium term allows them to pay the expenses of their operation, but not the interest on their debt. Another way of looking at them is that the ability to repay your debt with your cash generation is unlikely.

Some authors define them as companies with an interest coverage rate (BAII / Financial expenses) less than 1 and a Tobin's q (market value of the company / book value) below the median.

An important part of the COVID-19 loans has reached both companies that were already zombies and those that have been converted due to the changes in their business models due to the current situation. This has generated an increase in this type of company in Spain and in several countries of the world.

Can we have an idea of the number of zombie companies in Spain?

There is a dance of figures between the Bank of Spain, the IMF, the EIB and some experts.

The Bank of Spain considers that in Spain there are 40% of companies with high financial pressure and 19% of insolvent companies. By sectors, the most critical are the hospitality industry, in which 72% of companies have financial pressure and 33% are insolvent, and the motor vehicle sector, in which 64% of companies have financial pressure and 32% are insolvent. However, this simulation assumes that the future results of the companies will be the result of a 3-to-1 weighting between the 2019 and 2020 results, which represents a quick return to the path of pre COVID-19 results. In other words, with a slower recovery, the estimate would not apply to and the percentages of insolvent companies would be higher.

Banerjee and Hofmann consider in their paper of September 2020 that in Spain we reached 17.5% of zombie companies in the decade 2010-19. It is common sense that this figure should be higher in 2020-21, especially if we take in account that the study was based on listed companies.

This percentage is similar 17.6% that Iber Inform raises for the end of 2020 in its 2018-19 balance sheet study. This estimate should also be higher given that the study only considers companies that have submitted their books for registration, being the zombie companies more reluctant to comply with this practice.

Thus, according to the above, the percentage of zombie companies out of the total would be in ranges above 18% by 2021.

But what risk do these companies have of disappearing?

Returning to the Bank of Spain, this entity predicts that more than half of the insolvent companies will be unviable (negative long-term results).

This leaves in the best of cases a percentage of unviable companies higher than 10%, and by sectors most affected of up to 17%.

And it is in the best of cases because the main factor that can make these companies leave their state is to return to the path of profits quickly, which is not what the growth of Spanish GDP indicates. Given that the really strong growth in GDP will only occur in 2021 (7.2%), if the zombie companies do not manage to overcome this year, it will be difficult for the following ones.

The authors Banerjee and Hofmann conclude that 60% of the companies that have been zombies have survived, but once again this study does not consider small companies, only takes in account the listed ones. And for this data it is based on long series from many countries, generally more solvent than Spain and with more efficient restructuring systems (Japan, Germany, Canada, etc.).

In terms of size, small zombie companies disappear more easily and faster than large ones.

Small companies do not have economies of scale, the possibility of undertaking professional turn around, hiring expensive management teams or accessing resources that have minimal fixed costs. On the contrary, the large ones have easier refinancing than the small ones: greater lobbying of the owners, the banks are more inclined to put up with them to avoid provisioning large amounts on the balance sheet, and the social and political impact of their disappearance is greater.

Non-bank fund raising for small zombies is difficult as mutual funds, family offices, and alternative financings seek minimal volumes in sales, assets, and EBIT.

And what can we expect to happen in Spain with this type of company?

In Spain there are several factors that are going to affect them in the short and medium term:

The first is the end of the bankruptcy moratorium for all debtors who had extended the obligation to request bankruptcy (voluntary bankruptcy), which prevented their creditors from making the request before this date. It was expected to end on March 14 and the Government will extend it, in extremis, until the 30 of December. All and with the moratorium, in the fourth quarter of 2020, 2,428 declared bankrupt, the highest figure per quarter since 2013 and one of the four highest since the Lehman Brothers crisis. Much worse numbers are expected by 2021: The Professional Association of Insolvency Administrators (ASPAC) considers that the number of tenders to which zombie companies are going to be doomed is overwhelming and the Council of Administrative Managers numbers 130,000 SMEs that are waiting to file bankruptcy if they do not get funding, which would be 20 times more than the companies declared bankrupt in 2020.

On the other hand, on May 31 the period to qualify for ERTE ends. The most obvious consequence of the termination of the ERTE is the reinstatement of workers to their activity and the consequent obligation of the company to pay the payroll again. In December 2020 there were 782,915 people in ERTE, and the hospitality industry concentrated one in three people hosted by, with 241,390 people. If the Government does not decide to extend it again, the zombie companies will increase their salary costs dramatically, making the situation even worse.

The third milestone that will put this already eroded productive fabric in serious difficulties will be the beginning of the repayment of the debt of the ICO loans. The self-employed and Spanish companies received last year a total of € 114,647 million in 944,588 operations. Although the Council of Ministers extended the grace period to two years to begin repaying the debt, these must begin to be repaid as of March 2022, with a maximum horizon of 8 years.

We will have a fourth milestone with the entry into force of the Basel III standards, postponed until January 2023. These strongly affect the core capital of banks, increasing their percentage and need for equity, as well as imposing greater prudence and rigor in granting credit. This new policy will condition the refinancing of zombie companies, which will become almost impossible and lead to bankruptcy for many of them. Worthless to say that the more and more probable inflation may lead to increase in banking rates, that will add pressure to the P&L of this type of companies.

All of the above leads us to think that zombie companies, which are increasing in number, are going to have even more difficulties than up to now and be doomed to disappear in the next three to five years.

And in parallel, it leads us to consider whether or not the M&A should focus on these types of opportunities, that is, whether it is worth acquiring zombie companies as opportunities and / or to strengthen investee portfolios.

In the next article we will analyze success stories of Spanish companies that have come out of their zombie state and the ways that Spanish legislation has provided so far.